In 2017 I applied for and received an Engine micro-bursary from New Art West Midlands to visit the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Austria, in return for writing a report about it for those back home.

The report is here and archived below.

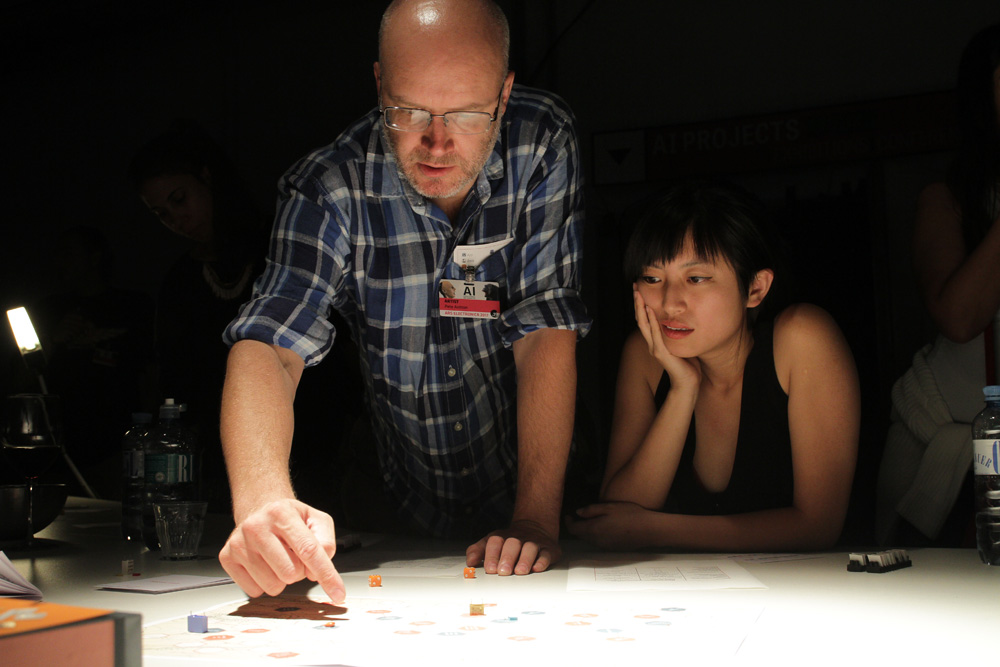

Due to my Linz residency in 2016 I was able to stay with the qujOchÖ artist collective who invited me to be part of the performance of their game Myth of Theuth, which got me accreditation as an Artist, which was nice.

Pete Ashton on Ars Electronica, Linz

Ars Electronica is a large media arts festival and as such it functions like most large industry gatherings, albeit with a less rapaciously commercial imperative. It takes place in the city of Linz, the third largest in Austria, roughly 2/3rds the size of Wolverhampton, give or take.

Ars Electronica (commonly shortened to Ars, which makes smutty British people snigger at your visiting Arse) was founded in 1979 and is based around the Ars Electronica Centre, a science museum for future technology manifesting as a glowing cube of flashing lights on the banks of the Danube. It appears to house very little art, which is a bit confusing when visiting during the festival, but uses what you might call a cultural mindset to frame the exhibits on show. There’s also a strong emphasis on pixels and screens. Lots of VR goggles at the moment alongside their much vaunted “8K Deep Space” room where multiple high definition projectors fill the wall and floor like a slightly more immersive IMAX. Like most “big telly” spaces in cultural institutions, the challenge seems to be figuring out what it’s for. Maybe it’s just a big telly.

This “future technology” thing sometimes makes the place feel old fashioned, a problem futurism has bumped into in recent years. As we fumble our way through the end days of neoliberalism it’s harder and harder to imagine a future that isn’t part of our tattered reality tunnel, so futures that wish to avoid doomed dystopic nihilism have to remix the past, only smaller and faster and with more pixels. Ars gamely tries to bring earnest social concern to their tech evangelism but to these jaded eyes it feels a bit naive. Still, it’s refreshing to see a European take on what has become dominated by The Californian Ideology.

While the centre runs all year, the festival takes place for a week in September, and in recent years has completely separated from the mothership, occupying Postcity which is not a new space for exploring post-city ideologies and is actually an empty disused post office sorting depot. This is oddly refreshing, like discovered something called an Innovation Centre was actually used for innovation, which never happens.

The space is vast, covering three massive floors, some still kitted out with conveyor belts and mail sorting chutes, down to the ominously named Bunker complex which feels like a cold-war installation. It’s on a scale with a convention centre, but without any of the facilities. Ars brings it to life once a year, filling it with industrial fittings to create stalls, booths and workshops while decorating the concrete with potted long grasses. The end result evokes a post-industrial takeover by a tribe of techno-futurists, especially when all the Media Artists arrive with their fashion cliches and quirks.

You enter at the top floor via a sweeping service road built for lorries and collect your badge, although this is not technically needed for the top floor which is open to all. This floor is roughly divided into two areas. First is what I call the Tech Demos, works by artists that show their workings more than their meanings and which might lead to greater things in time, and demonstrations of cool technologies with no pretensions of artistry.

The former included most of the Artificial Intelligence which, to my mind, still hasn’t produced a great work yet. They’re using an artistic approach to poke at this relatively new technology and reveal some of its weirdness, and that’s great, but I doubt any of the artists involved are satisfied yet. There’s more work to be done. The later reflects the main Ars centre. Lots of mind-control headsets, lots of robot arms, all very wow but of very little substance. But that’s fine. We don’t always have much wow in our lives. Often wow is enough.

Downstairs is what you might call the real art. Threaded through the maze of tunnels are installations and curated exhibitions, some commissioned by the festival along with a collections from commercial galleries across Europe. Developing the market for digital art, often by definition intangible, is one of the the strands at Ars.

The art on show was on a very high standard. I was particularly impressed the following:

- Stefan Tiefengraber’s Delivery Graphic

- Gaybird’s Fidgity

- Akinori Goto’s Sculpture of Time

- Gil Delindro’s (Un) Measurements

- Robert Andrew’s Data Stratification

If the upstairs was a fun-house of excitement the downstairs more that made up for that with plenty of space for contemplation.

Of course, one man’s impression of a massive event like this is going to be subjective and informed by my state of mind. While I had the eye of a practitioner I also had the attitude of a tourist, so I was interested in how the locals felt about this whale of a festival landing on their town.

Last year I was in Linz for a residency run by qujOchÖ, a collective of local artists that’s been working in the city since 2001. When I said I would be returning for Ars, one of the founder members, Thomas Philipp aka Fipps graciously said I could stay with him. This, coupled with my introvert approach to mingling, meant I followed qujOchÖ members around like a lost puppy, giving me something of a grass roots view of the whole affair.

Austrians, it turns out, are famously cynical and grumpy (their term “sudern” is hard to define but is rather like a Gaelic shrug soaked in nihilistic disappointment) so it wasn’t too much of a surprise to hear the local artists bitching in the bars late at night about programme changes and managerial incompetence. And I’m sure you’d hear that in any city - big events are hard and toes will be trodden on.

But I was surprised as the lack of impact on the local scene. I would have thought this would be their tentpole event, a chance to show off local work to a visiting global audience (and Ars is truly a global affair). But the impact was negligible. A lot of people got technical work, of course, and one of the shows at the main art museum was by a dystopian docklands by local collective Time’s Up (which had an oddly English vibe I felt), but this was an anomaly and where the Linz scenes were represented it was on the unofficial fringe where business was as usual.

Maybe the effect of Ars happened years ago and the city is now sustainable without it, allowing the festival to become a transnational entity, bringing inspiration in rather than exporting it. The local artists are complacent about it because it’s normal. Surely every city has a massive, international, popular, thoughtful and, most importantly, competently run arts festival? Sadly, they don’t.

If Birmingham had the equivalent of Ars Electronica (ignoring for the moment that this city is currently financially, ideologically and structurally incapable of such a feat) it would change everything for the artists working here. Not just from the sense of having an infrastructure or an income but from shifting our horizons and giving us a global perspective on our work.

Interestingly, a couple of months after Ars, Coventry had it’s first Biennial centred on an exhibition of contemporary art in an empty newspaper print-works. Despite the grand name (Biennials make one think of Venice) it was a totally grass-roots, shoestring budget affair, utterly hooked into the local art scenes. It was fired not by routine or remit but by a passion that, fuck it, this needs to happen and we can make it happen. The Coventry Biennial, should it continue and grow, will bring stability and continuity to a community of artists that will raise their game. And should it succeed beyond their wildest dreams, those same artists will kick against it, sneering at its conservatism and conformity, at its inability to react and embrace what’s happening in the city it helped to transform.

And that’s exactly the way it should be.