Sometimes you want to give a talk on a subject but you can’t quite structure a talk from the subject in the way you’re supposed to, so you just give an unstructured talk and see how it goes.

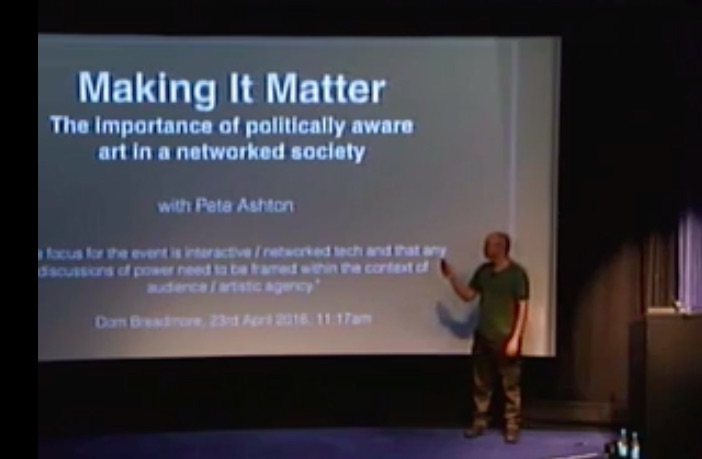

Making it Matter was a talk I gave for the Random String conference in Coventry on June 10th 2016. Random String is an arts conference concentrating on technology and involves a number of my peers from the West Midlands.

I wanted to talk about the ethical and moral struggles and compromises necessary when working with technology. This is, of course, a massive thing, but I felt it was important for these issues to be raised at a technology conference where speakers tend to be understandably positive and optimistic about the tools they’re using in their work.

I think the talk went down OK. I had some nice feedback afterwards. But as a “performance” it’s very lacking. Later I discovered the problem is it doesn’t obey the Monoform, which I wrote about in 2018, referencing this talk, and have reposted below.

The Monoform could be called the Varnished Truth, where all the unfortunate, difficult bits are smoothed out to leave a perfect, coherent statement. But truth isn’t coherent, and art is messy, so maybe we need less varnish at our conferences.

Looking back on this talk in 2019, when I first wrote up this page, I was quite impressed at how I started to articulate some of these points. I was definitely on to something and was sure I could do a better go at it, should anyone want to give me a stage and half an hour.

Public Speaking and the Monoform

Nov 27, 2018

Maggie Mae Fish’s analysis of the fascism in Fight Club contains multitudes and is well worth your time if you’re interesting in how what seemed like a slightly heavy-handed piece of dark satire in the 90s has become a bible for some young men in the 2010s, effecting a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, but there was a bit 26 minutes in that really caught my attention because it put a name on something that’s been bugging me for a few years now regarding the plethora of educational and inspirational talks that get given at conferences and elsewhere, and of which I have given many.

It’s Peter Watkins’ idea of the Monoform, “a linear pre-determined format meant to drive the audience towards a specific conclusion”, which Maggie says Fincher is consciously using to create a fatalistic, inevitability to the whole thing.

I do a fair bit of public speaking, and because I’ve done a lot I’m fairly good at it. I know how to carve 30 minutes into a narrative that drives the audience towards a specific conclusion. A conference talk can usually be broken down like so:

- I’m going to tell you about Z

- But first let me tell you about W

- W often leads to X, especially when you consider A

- A leads to B, which in turn often brings about C

- C is analagous to Y

- And Y, as you’ve probably realised by now, takes us to Z

- Thank you and applause now please.

It’s all very linear and clean, like building something with lego. Everything fits beautifully into place. This is OK when the speaker is trying to communicate a complex idea, or at least lay the groundwork for a complex idea. I use it a lot when I want someone to understand something like photographic exposure, breaking it down into simple concepts and then putting them together in a linear and clean way. It’s a very valuable tool.

When it gets mildly troubling is when the speaker is telling a more personal story. I’ve seen it a lot at culture conferences where some artist or creative is using a platform to raise their profile, because you’d be a fool not to at those sorts of events, by showing their work. It’s often monoformed to the max, turning the doubtless messy and confused practice of creativity into a hero’s journey.

You also see it where speakers are often required to be motivational, to leave the audience inspired. You don’t do that by being vague and uncertain. You do that by finishing with a neatly tied bow.

I discovered this when I gave a talk a couple of years back where I deliberately didn’t have a conclusion, because the subject I was talking about felt too complex. I wanted to bring some questions to the conference without answering them and while I made a passable attempt, how do you end a thing like that? You can’t just stop. You need to conclude. So I concluded by going all meta about how this is where I’m supposed to conclude, which gave me the seed of a mini-monoform letting me finish. But it was a tough one and certainly not one of my best. You can watch it here, scraped from the livestream. The last five minutes are the most germane here.

I enjoy public speaking, because I enjoy the monoform. We’re hurtling towards a very specific destination and it’s my job to get us there in an entertaining and illuminating way. Yes, I could tell the story differently. In order to gain clarity I had to edit tricky facts and smooth awkward events. When it works, a good talk is like an abstract sculpture. But it’s not real. It’s not truth. It’s a story in service of something.

Always be aware of what that something is, and judge accordingly.