In 2015 I became interested in how people were sharing images on Instagram, a platform which did not allow reposting or reblogging which was the dominant form at the time thanks to platforms like Tumblr and Pinterest. You could fave something on Instagram but not move it into your own stream easily. Apps were available but they were fiddly. The simplest way was to take a screenshot of your phone and repost that, cropping out the surrounding interface as accurately as you cared to.

This process invokes all manner of image transformation and compression processes which mean that, in theory, each reposting of an image is in some way unique. This is not unlike the photocopying of a funny cartoon found on an office noticeboard in the 1980s, off-centre and greyed out having been through the copier countless times.

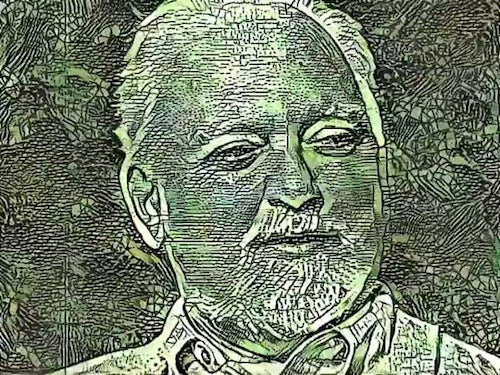

Brian Feldman also noticed this trend, coined the term Shitpic and wrote a wondeful article about their rise and meaning:

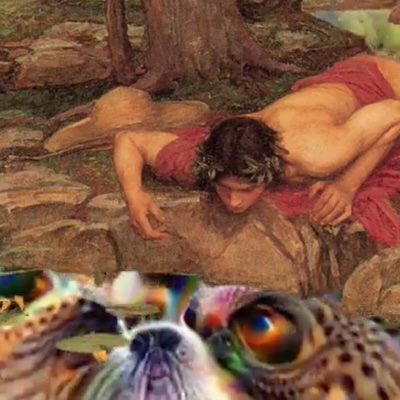

When you pair the format’s inherent need to be screencapped in order to attain virality with Instagram’s prevention of downloading images, you get an endless cycle of screencapping and compression through uploading. Throw in the occasional filter, or watermark, or regram tag, and let the process carry itself out for a while, and eventually you get a Shitpic. The layers pile up, burying and distorting the original.

The rise of the Shitpic demonstrates just how little ownership there is on the internet: Shoddy workarounds and subpar image quality are a small sacrifice to make, so long as your version of a joke goes viral instead of someone else’s. That the image is a muddled cacophony of compression artifacts and blurry emoji matters little, so long as your screenname is above it.

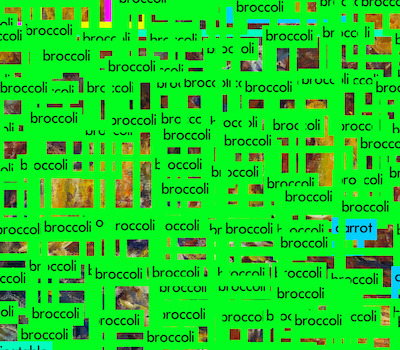

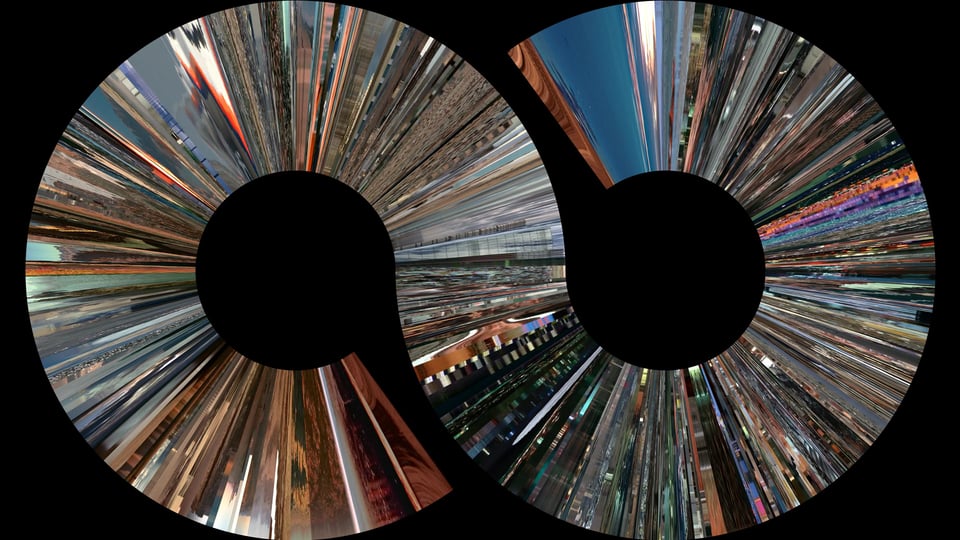

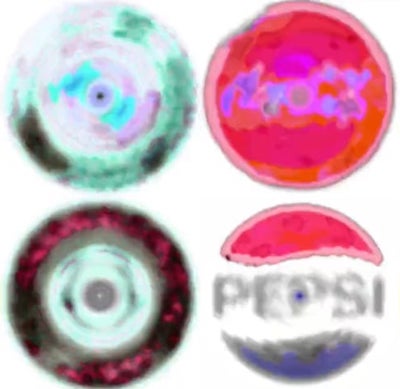

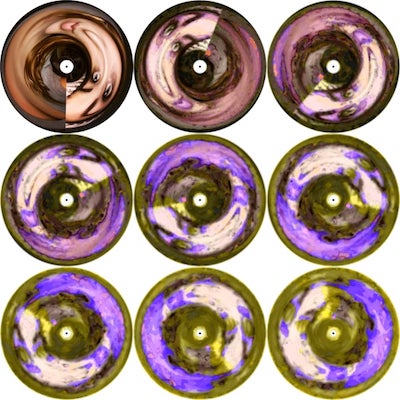

During this period I was downloading lots of selfies from Instagram which inevitably involved clearing out wrongly tagged images, and came across the Which Am I Most Like? meme. I noticed that most of them were reposted in this way and had subtle differences, so I set my robot up to download as many as it could.

I put the results in an HTML table which embeds the images as binary data so they are exactly as they arrived on my computer in rows for each type. “Typologies” refers to the work of the same name by Bernd and Hilla Becher.

My intention was to present them in some more aesthetically pleasing way that somehow measured their uniqueness, but I never did.