Echo Edit

A key part of Instructions for Humans saw me collaborate with performance artists. In order to work with those artists I needed to put myself in their shoes to properly understand what I’m asking them to do. I need to become a performance artist.

Echo Edit was proposed as a durational performance piece in response to an open call for It’s Alive! put out by local performance art collective Home For Waifs And Strays and experimental film night Magic Cinema on the theme of Live Art + Cinema.

Echo Edit was my first piece of public performance art. In recent years I’ve become interested in the medium, mostly because I don’t understand it and find some of it impenetrable and uncomfortable. I think embracing these feelings and integrating it into my own practice might be useful, possibly in the same way I found hanging around with sound artists made me think about photography (light art, if you like) in new and exciting ways.

Merging performance and data art is not a new thing and there are a few artists and works I’ve seen over the years which have pushed me along this path.

Inspiration

Transcranial, a trio of pieces by Klaus Obermaier, Daito Manabe and Kyle McDonald, which I saw performed at the Resonate festival in 2015, was all about the live collaboration between dancer/performers on stage and programmers in the wings. For Klaus Obermaier’s section a video feed of the dancers is fed through algorithmic processes and projected onto the stage. The dancers can then “play” the algorithms by altering their movements, while Klaus tweaks or switches the algorithms to “play” the dancers. Equilibrium is found and lost as the performance plays out.

Emily Warner was one of the other artists on the Goodbye Wittgenstien residency in Austria last year and is exactly the sort of performance artist that confuses the hell out of me, though I do enjoy her work a lot. Working alongside her for that month was really illuminating and our conversations have led to her being one of the main collaborators for Instructions for Humans. Mostly it’s the procedural, ritualised nature of her work and how she responds to a space or object with movement. I see parallels to the act of photography, which is really interesting.

This year, again at Resonate, I got onto the Hacking Choreography workshop with Kate Sicchio, a dance choreographer and tech-artist who has connections to the live-coding Algorave scene. One of her pieces, Hacking Choreography, sees her use a human-readable pseudocode to give instructions to dancers, defining moves and setting “if-then” loops. Other than the insight into choreography and scoring movement, it was good to get a sense of how the human performer relates to the process and the freedom of interpretation they have. The work is not scored in the sense of an orchestral score where players (within reason) have to do as they’re told, but scored in a more suggestive way, creating a dialogue through the code and their response to it. In other words, the dancers can ignore their instructions, which is as valid a feedback signal as obeying them perfectly.

Memo Akten’s Simple Harmonic Motion #12 was a performance piece commissioned for the Future Everything festival in Manchester which I saw in 2015. A row of 16 percussionists played a simple rhythmic piece which fell in and out of phase (a la Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music). Each player was responding to a click-track playing in their ear which they had to replicate. Obviously some made errors, which gave what could have been a rigid, militaristic piece a sense of organic humanity. I really liked the use of humans as meat-circuits in a mechanical system and the requirement that they not be perfect. (Memo has recently been developing work using machine learning and computer perception so the thread from the SHM series is nice to explore.)

Obviously there’s more to each of these than the sliver I’m highlighting here for my personal use and I’d recommend exploring them further. And there were other people and things along the way, which I’ll doubtless remember once this is posted, but you get the idea.

Objectives

The purpose of Echo Edit was to force myself to be a performance artist so I could work with performance artists more collaboratively. If I am asking them to come into my world of data-art then I need to go into their world of physical movement. This is not something I find comfortable. While I do certainly use gesture and movement in my work (from gesticulating while teaching to the physical contortions needed to get that specific photograph) consciously making gestures without literal value feels very weird to me. When I dance it’s not deliberative or performative. It’s just dancing. This would be movement on purpose with no purpose. Weirdness.

I had put myself in a similar position on the Goodbye Wittgenstien residency while experimenting with new ways to render photographic data. The previous occupant of my studio had left some soft charcoal pencils, a medium I’ve never dreamed of using. The reason I use cameras and keyboards is I cannot actualise what’s in my brain with a pencil. I just lack the motor skills, I guess. But I can trace, so I projected my composite image on the wall and traced every detail. The process was fascinating as I was acting in a completely mindless way, like a plotter printer.

The resulting work was framed next to the original digital image in my section of our group exhibition. A lot of my work was algorithmic, in the sense that I was pushing stuff through a computational process to see what it would keep and discard (the original in this case was created by using Photoshop to merge lots of very different photos with the focus-stacking Auto Blend algorithm (see also)) and here I was using my self as a computation process. I see the shape, I move my hand to trace the shape. It becomes a very mechanical movement with little conscious thought, but the glitches and errors betray my character and humanity. Maybe.

This reminded me of a writing class run by Ken Goldsmith which he described in an interview I now can’t find, but the gist is he asked his students to copy a text word for word. In the process they made mistakes and errors. These errors were the interesting bit. He also talks in this interview about how “if you and I were to transcribe an identical conversation we would transcribe it completely differently. And so this is a validation of this kind of writing: people say that this isn’t writing; it’s merely transcription; but in fact it is very unique and individual writing.” Goldsmith is a prankster, but he’s a very serious one and he’s on to something here.

What is this sort of thing illuminating? In everyday activities we often perform mechanical gestures - think of swiping an RFID card to go through a turnstile or driving a car - but everyone does them differently. In fact, the more mechanical the gesture, the more someone’s personality can be revealed. Our personality is in many ways keyed up to how we interact with the objects of the world, be it the creases left on a paperback book or the smudges on a touchscreen.

As a data-artist (which I define as any artist who uses a computer at some point in their work) I construct systems through which data flows and is shaped. The data-flow for one of my photographs is usually Camera Settings > Sensor > RAW file > Macbook > Lightroom > JPEG > Internet > Screens with each stage seeing transformations of the data. But before the photograph there’s non-electronic data flow informed by the space I’m in: the light in that space, my location and position in that space, etc. Then there’s the camera itself which radically defines the sort of photography I’m allowed to do (See Vilém Flusser for more on this). And finally there’s the data-flow inside my brain leading me to decide what to photograph and how, informed by my mood, my ideas, my memories of the past and imaginations of the future. All of this is part of the system, part of the flow of making a picture. Why do we separate the human, mechanical and data parts so rigorously? Would it be interesting to blur them up a bit?

In essence, technology doesn’t dehumanise. Rather it serves as an abstraction tool to reveal the nuances of humanity. So let’s put humans in the middle of otherwise mechanical systems and see what happens.

Documentation

Echo Edit was proposed as a durational performance piece in response to an open call for It’s Alive! put out by local performance art collective Home For Waifs And Strays and experimental film night Magic Cinema on the theme of Live Art + Cinema. Andy Howlett, who runs Magic Cinema, had been interested for a while in the potential of combining the spontaneity and fleshiness of live art with the premeditation and mechanically mediated atemporality of cinema (though I doubt he’d put it quite like that), resulting in a Dream 53, a performance of a “lost” surrealist film for the Homegrown project.

The open call read as follows:

Home For Waifs and Strays are joining forces with Magic Cinema to put on an event that breaks down the boundaries between performance and film.

We are looking for short performances designed for film, live art incorporating film, cinematic performances, performance documentation, performance in dialogue with film, and any other live art/film mutation you can conceive.

My proposal was this:

Experience the history of cinema editing itself into a unique narrative through the medium of human gesture as artist Pete Ashton, connected to a gesture control system, allows the movies to control his movements.

An experimental piece using the Wekinator gesture recognition programme and an archive of movie files. As a section of a film plays on the screen I will echo the movements of an actor. My movements will be recorded by the computer and translated, via Wekinator, into instructions to select which film to play next and where to start (eg, film 23 at 45 minutes in). I will then repeat my mimicry until the system is triggered and a new film starts.

The work will therefore comprise of randomly juxtaposed scenes from a wide range of films accompanied by a live human performance informed by those films. As my movements will be directly informed by the footage on the screen, the films themselves will be authoring their edits.

As part of my next body of work, Instructions for Humans, I will be developing work where humans learn from machines and vice versa. This will serve as a simple test of this concept.

Which remarkably, given I wrote this in an evening and had no real idea if it would work, is pretty much what I did.

Jumping to specific points in films was the hardest technical challenge. A movie is a big file, and getting a computer to load hundreds of megabytes every few seconds is a massive ask. So resized and recompressed the movie files and then sliced them into small chunks. I used ffmpeg to slice the movie at every keyframe meaning the chunks aren’t all the same length but had the advantage of usually starting at a change of shot. Here’s the ffmpeg command I used, should you ever need to do this.

for file in *.mp4; do mkdir clips/${file%.m4v}; ffmpeg -i ${file%.mp4}.mp4 -acodec copy -f segment -vcodec copy -reset_timestamps 1 -map 0 clips/${file%.mp4}/${file%.mp4}-%d.mp4; done

(The logistics of movie compression are fascinating but that’s a subject for another day.)

I processed some 30-odd movies, removed the credits and grouped the clips into 12 folders with 5,000 in each. (I was aiming for 100 movies but time ran out, and frankly 60,000 clips is plenty!)

Next I threw together a quick PureData patch to load and loop each clip for a fixed number of seconds. Initially it generated two random numbers between 0 and 11 and between 1 and 5000 which combined to reference a movie clip directory and file (eg 5/2633.mp4) but random was only good for testing. I needed to bring the human in.

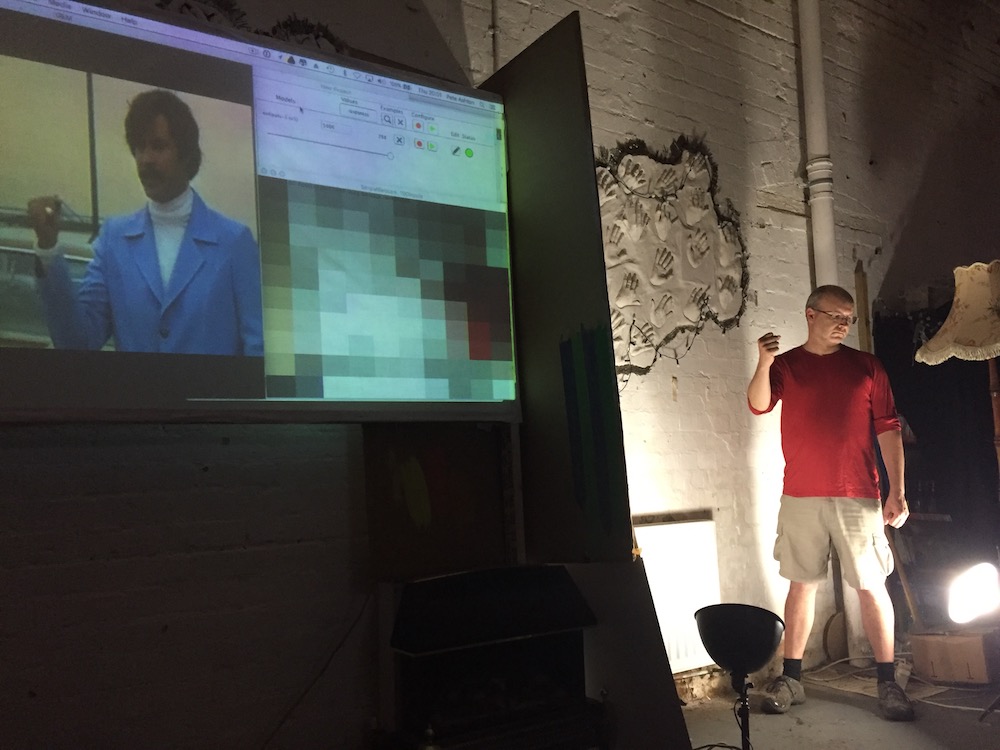

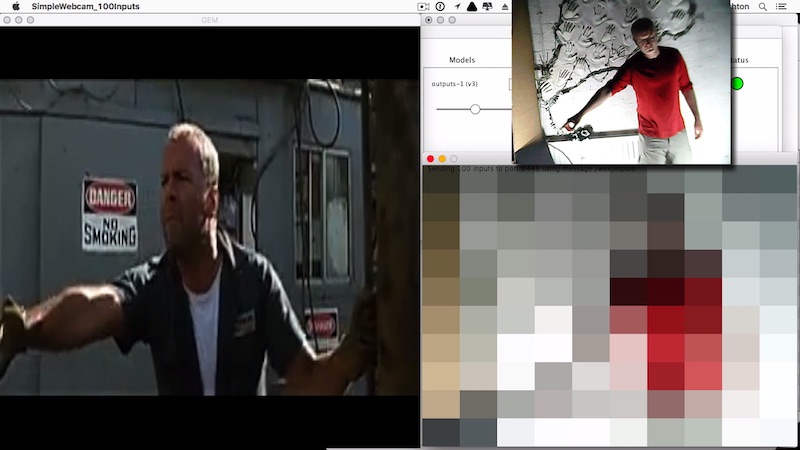

To do this I used a couple of applications. The first was a simple webcam app which converted the stream to a very low-resolution 10x10 grid of blocks. This means rather than sending all the video data it just sends 100 numbers per frame which is much more manageable. It also has a really nice aesthetic. (In the screenshot below you can see the 10x10 grid in the bottom right with a normal webcam shot above it. On the right is a movie clip.)

The webcam app sends these 100 numbers over the OSC protocol to the machine learning control application Wekinator.

Wekinator is a tool for converting a fuzzy signal into a number which can be used to control another programme or instrument. For example, waving in the top-right of a webcam view can send a number to a synthesiser which triggers a high-pitched tone. There’s some good examples of Wekinator being used for musical instruments here.

Wekinator is very easy to use but I had trouble getting meaningful numbers out of it, mostly because there was no meaning inherent in what I was asking it to do. I wanted particular gestures and shapes that I made to give me a number from a specific range, but that meant I either wasn’t accessing the full range of files or, worse, that any gestures I hadn’t trained for weren’t generating anything.

What I should have done, and will do when I do this properly in August with Emily and Aleks, is use a machine learning system to analyse the gestures and shapes in each movie clip and assign them a reference. The same system would then analyse me on the fly and compare my reference to the database of clips, loading a similar one. That way there’d be an explicit connection between my gestures and the order of the movie clips.

This didn’t happen in Echo Edit as I was effectively acting as a human random number generator, within some arbitrary ranges. Whether this was a problem or not is a very interesting question though.

I performed for an hour with a couple of technical breaks and ended up with 40 minutes of recorded material.

Given I felt like I was just generating random numbers, I tried removing Wekinator from the system for the last 10 minutes (starting here) and reverted to my test system where my gestures had nothing to do with the random selection of clips. To the audience this made no difference and looked exactly the same, but I was interested to know how I’d feel not being part of a loop. The knowledge that I was or wasn’t generating the number which loaded the next clip was strangely important. For the first 30 minutes my movements, however meaningless, were part of a system and therefore important. If I wasn’t there the system would just play the same clip over and over. With the computer generating random numbers to load without me I was utterly disposable and my actions pointless as well as meaningless.

I moved from thinking “I could be replaced by a machine” to “I have been replaced by a machine” and it felt bad.

Conclusion

I’m reluctant to draw any solid conclusions from this as it was mostly about the experience of performing the work and those feelings are very subjective and fluid. It’s more interesting at this stage to simple say what happened and why.